- by Amanda "Mandifesto" Orneck

- Posted on April 16, 2012 @ 2:00 PST

Journey

Genre: Puzzle

The ESRB has rated this product:

Everyone

Everyone

03/13/2012 ( PlayStation 3 )

Desc:

An interactive parable, an anonymous online adventure to experience a person’s life passage and their intersections with other’s. Experience the wonder. Discover the journey.

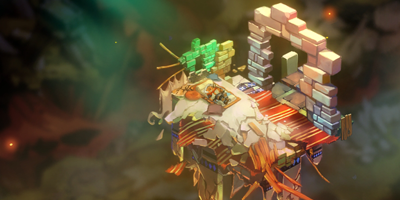

To anyone familiar with thatgamecompany, Journey is more than a video game: it’s a metaphor for the company itself. Each title Jenova Chen offers is one of simple delights and small brilliant moments, and Journey is no exception. The game takes only a few hours to play, but as with most artistic achievements, the experience is deceptively simple.

Tribal, cubist, alien, and ancient

It’s a wonderful thing to say that we have reached a point in our society’s technological development where some games resemble fine art. Journey is a great example of this. Not only is this a beautiful game visually, but the visceral feel of traveling over the dunes, being pushed along by powerful winds – all of it is beauty incarnate. The visual design of this game is essentially simple: Character models are made up of loosely conjoined geometric shapes, but underneath that simplicity is an almost cubist sensibility to the art that at the same time stirs up imaginings of cave paintings from long ago.

The musical score adds to the tribal feeling of Journey. The melodies are haunting, the chanting voices, devoid of any discernible language, instill in the player that they are either witnessing something very alien, and very ancient.

This is a much larger game than Flower, at least in terms of level design. As you progress through levels you cover huge expanses of terrain, vast desert plains and craggy peaks, deep canyons and dark pits. Always though, your goal looms ahead of you – the cracked mountain.

Joining others with deceptive ease

Another divergence from Flower can be seen in Journey’s control scheme options. You can still opt to use the SIXAXIS control, but there is also the option to use the thumbsticks to control your wondering hero. The theme of Journey, as was mentioned before, is “deceptive simplicity.” This applies to all aspects of the game, gameplay included. On the surface this is just a game about moving through a desert environment toward the goal of the cracked mountain. As you move along you’ll encounter glowing runes that extend your scarf – the source of your special jumping and flying abilities. The longer the scarf, the bigger the jumps you can make. It’s all very basic.

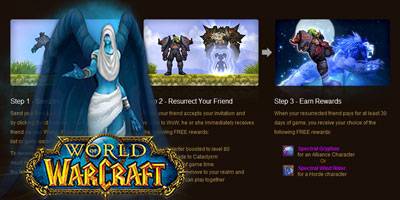

The brilliance comes into play when you realize that somewhere along the lines you have picked up a partner. A second player joins you in one of the earlier stages, and together you have an easier time navigating the stages. By sticking closer to this coop partner you continually charge your scarf, and the game simply becomes easier. This seamless multiplayer element is just as easy as the control scheme in the game: Your partner appears, you team up and finish the game together. As you progress through each stage, you will play with a variety of people, who drop into the game automatically, communicate only through jumping and small musical blips, and leave your life just as easily.

From a programmatical standpoint this system must be incredibly complex, but the player never sees that. All of the work happens behind the scenes, and it lends to the feeling of an “alien and ancient” world first built by the visual and auditory design.

Up to the player’s interpretation

One could almost merge a discussion of story with discussion of the visuals of this game, that’s how intertwined they are. For one thing, the majority of story is told through cut scenes and wall paintings showing your progress toward the cracked mountain. Because this is a game devoid of voicework, all the storytelling is done visually, and therefore is a little more challenging to follow. You can tell that your character is meant to travel up the mountain, and that your mentor (mother?) is there to guide you along the way, but little more information is given.

The paintings are also a gameplay element, since in various stages you can uncover drawings that hint at how to progress through the levels. Because of the tribal nature of the drawings in these maps, they also feed into the larger story, telling about whatever ancient world you are traversing in your expedition to the cracked mountain.

The deeper themes of perseverance, heroism, chivalry and cooperation are seen throughout the game, as you help not only other players, but magical creatures that seem to be made from the same fabric your scarf is woven from. One can tell that the main character is meant to be both heroic and altruistic because of the great sense of reward you receive with you free these flying creatures. They in turn help guide you through the levels, and even charge you with their musical birdlike calls. Knowing that this ruined landscape was once home to such beautiful creatures helps inform the story of what you yourself are doing in this world. But the ultimate story, the game’s ending, and the consequences for that ending, are very much up to the player’s own interpretation. Because ultimately, this isn’t a game about the goal, it’s about the journey.

Flawless brilliance

There are no flaws in Journey from a quality standpoint. Perhaps this is because of the small nature of the game, but more likely – especially when you consider the coop systems running in the background – this is a sign of the high standards that the developers hold themselves to.

Simply, a work of art

Journey is, simply, a work of art. The best art speaks to the observer and tells them more about themselves that the artist, and allows them to interact with it in a way the informs their perception of the world around them. While each part of the game it itself stunning, it’s the combination of all of these elements – from the visuals to the complex coop design – that truly makes this game beautiful. And best of all, its cyclic nature lends itself to endless replayability since the people you encounter will be different each time you play it, and therefore the journey itself will never be the same.

tl;dr - Too long; Didn't read

A masterpiece of deceptive simplicity, Journey is a work of art every PlayStation owner should experience at least five times.

Aesthetics: 5.0

GamePlay: 5.0

Story: 4.5

Quality: 5.0

Overall Score: 5.0

2 Comments for this post.

[Arturis]

@

4:54:20 PM Apr 16, 2012

To say this game is stylishly breathtaking would be an understatement, and the screenshots barely even do it justice. This is a game that needs to be experienced.

[Mavlock]

@

2:54:20 AM Apr 16, 2012

I hate exclusive titles, specially ones I want to play on consoles I don't own.

You must be signed in to post a comment.